Helping Libya after Derna

Since 2011, Libya has been in turmoil. Traditional divides between Tripolitania in the West and Cyrenaica in the East have deepened, compounded by foreign interference. Since 2014, Libya has de facto two Parliaments, one in Tripoli and the other in Tobruk. As is all too often the case, internal rifts attract outsider meddlers, and the country has repeatedly been flooded with weapons, mercenaries and foreign terrorist fighters.

Several unsuccessful attempts to reunite the country

Several attempts to reunite the country under a single authority, brokered by the UN and other international facilitators, have only provided temporary relief before divisions re-emerged. In recent months, tensions have unfolded again, culminating in a new oil export blockade and another outbreak of violence among armed groups in Tripoli in August. This renewed crisis has drawn again attention to the unsustainability of the status quo and the urgency of resolving the current political stalemate.

“This renewed crisis has drawn again attention to the unsustainability of the status quo and the urgency of resolving the current political stalemate.”

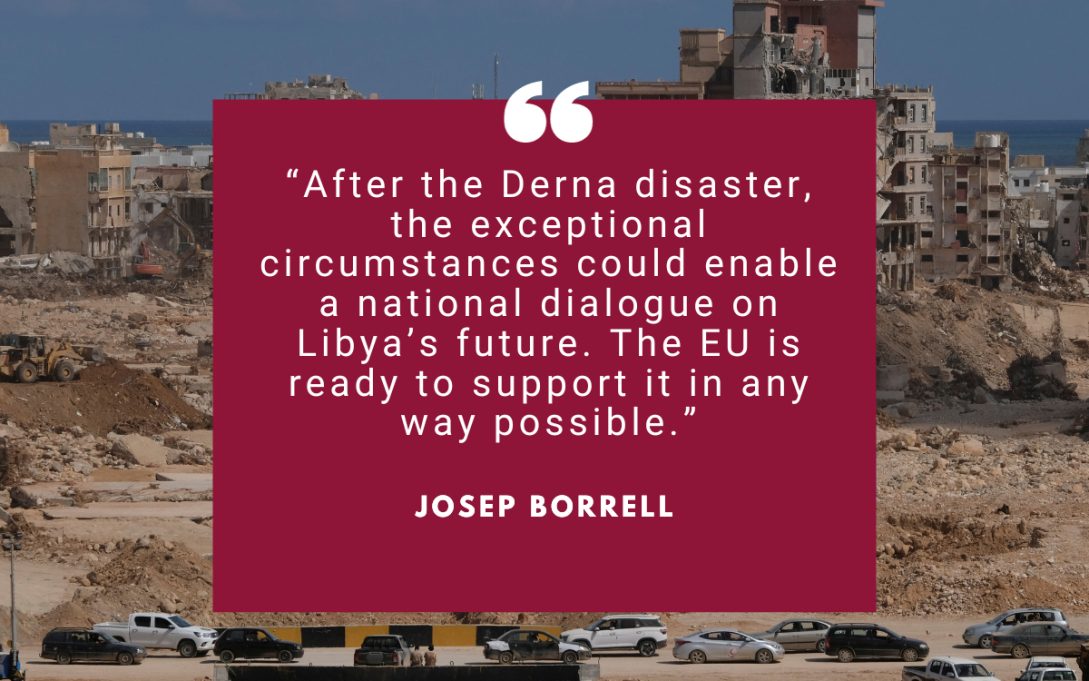

Then Storm Daniel hit the country leading to the catastrophe of Derna in the East. Extreme rainfall and poor maintenance led to the collapse of two dams upstream of the city. As of 19 September, more than 4 000 persons were confirmed dead, thousands were still missing and over 30 000 displaced. The EU Civil Protection Mechanism has been immediately activated and 10 of our member states have offered assistance via this mechanism accompanied by EU humanitarian funding.

This disaster has exposed a flagrant governance failure, prompting public outrage and reigniting a ‘blame game’ among Libyan politicians. The Libyan people's demands are clear and legitimate: greater transparency, greater accountability of the political class towards the population as a whole.

“The Libyan people's demands are clear and legitimate: greater transparency, greater accountability of the political class towards the population as a whole.”

However, there is a silver lining. The natural disaster has also created an extraordinary sense of national solidarity across the country and prompted new signs of cooperation between the West and the East, which has enabled international assistance, including European aid, to arrive and be effectively distributed. There is some good news on the economic front as well. In July, a High Financial Committee was established, tasked with ensuring an equitable distribution of State resources. Second, at the end of August, the Libyan Central bank announced the reunification of the current two – East and West – branches.

Libya does not lack of resources

These positive developments are crucial steps since the country does not lack resources. As one of the largest oil exporting nations, Libya has the potential of becoming a prosperous country again soon – provided political leaders across the country cease their infighting and make their top priority to meet the legitimate expectations of the Libyan people. West, East, and South need to work together so that all Libyans can benefit from the country’s wealth.

The disaster of Derna has reinforced the need for ensuring accountability, the key challenge that Libyans expect to be addressed. While central institutions are fundamental for ensuring a fair distribution of resources between regions, proximity to those concerned through decentralisation has proven a useful way to enhance transparency and accountability of decision makers. The exceptionality of the current circumstances could create the conditions for a national dialogue on the country's future. In this case, the EU is ready to support this dialogue in any way possible, as we have done in the past.

“The exceptionality of the current circumstances could create the conditions for a national dialogue on the country's future. In this case, the EU is ready to support this dialogue in any way possible.”

EU support to Libya will not waiver, be it through direct assistance or through the UN, its agencies and the UN SRSG Bathily. The EU is the largest donor of the UN joint programme on elections (PEPOL) We are also funding many other UN programs aiming to help prevent and combat corruption, protect children and young people or strengthen primary health care. Beyond financial assistance and political support, the EU is also the only international actor actively contributing to the implementation of the UN arms embargo through the naval operation EUNAVFOR MED IRINI, mandated by the UN Security Council to inspect suspect vessels at high seas off the coast of Libya.

Last August, before the UN Security Council, UN SRSG Bathily called for a unified transition government to lead the country to elections. This government should be a technical one, exclusively tasked with overseeing the elections. I reaffirmed to my interlocutor that for us, a UN plan – based on dialogue between the main Libyan stakeholders – is the only option for finding a lasting political solution.

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of a cure

Finally, the lesson we can (re)learn from Derna, both in Libya and in Europe, is that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. The difficulties Libya has been facing for more than a decade to come back to stability, illustrates that if we, in the EU, want to avoid recurring major crises at our borders like the one we witnessed in Lampedusa end of September, it is essential to invest more politically and financially to help countries like Libya break the political and institutional deadlock in which they are often trapped. By the time an open crisis breaks out, it is often too late to take effective action. We need to act upstream, before we are compelled to act when many lives have been lost.