#FieldVision | In Kosovo, healing the scars of war is a daily task

Do you want to know what it looks like to work in a EU military or civilian mission? Field Vision brings a fresh and personal approach from the EU’s civilian and military missions and operations, sharing first-hand experiences from around the world and showing how European women and men contribute to global security, peace and stability. Stay tuned for more stories in the coming weeks.

'To remain a reliable and honest partner for its Kosovo rule-of-law counterparts, the European Union Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo, better known as EULEX, underwent a metamorphosis during the past three years. It is a multifaceted civilian CSDP Mission with many fascinating and unique responsibilities. Among these is EULEX’s work to support the search for the missing from the 1998-1999 war in Kosovo.

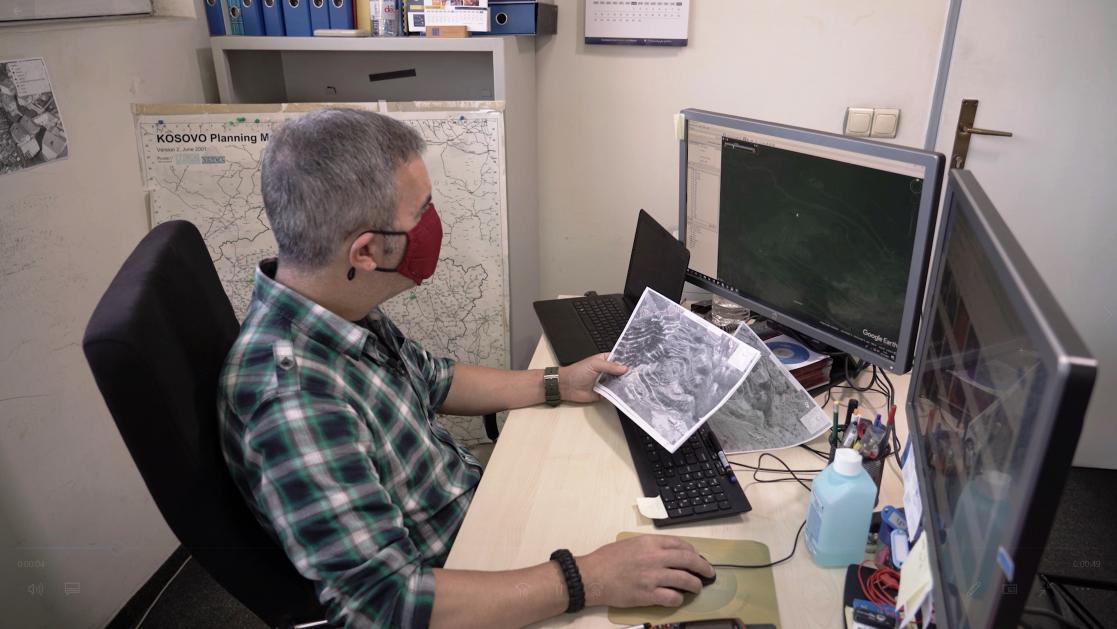

When I first joined the Mission in January 2020, I did not grasp fully the extent of the Mission’s work and its impact on ordinary people’s lives. A concrete example of the added value of the Mission’s mandate became clear to me in mid-November 2020 when I learned that after years of hard work and thanks to the use of aerial images, our experts, together with their peers from the Kosovo Institute of Forensic Medicine, the International Committee for the Red Cross (ICRC), and the Serbian Government Commission for Missing Persons discovered human remains in Kizevak, a large quarry site in southern Serbia.

Twenty one years after the war in Kosovo, the families of these missing persons would finally know the truth about the fate of their loved ones. Twenty one years is a long time, a very long time for a parent, partner or a relative to face the unknown. Unfortunately, this is not unusual in the Western Balkans. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, where I previously served as EU Special Representative and Head of the EU Delegation, families of around 6500 missing persons are still waiting for answers, just like in Kosovo where there are more than 1600 missing persons. Searching for the missing after an armed conflict is a painful, complicated and time-consuming process.

Missing persons is one of the most devastating legacies of the wars in former Yugoslavia. During the multiple conflicts across the region, bodies were often deliberately concealed to hide evidence and ensure impunity for the culprits. While trying to explain to me how difficult it is to find missing persons who are sometimes buried in ordinary cemeteries to disguise the war crimes, my colleague Javier gave me an example: “If I want to hide a book and make sure that it will be very difficult for anyone to find it, all I need to do is walk into a library, put the book on any shelf, and then walk away. To find this particular book, one needs to search shelf by shelf, checking everywhere, which will take a lot of time. This is how difficult it sometimes is to find a missing person buried in a cemetery.”

I do take pride in the fact that despite many difficulties, our Mission’s experts have conducted some 680 field operations to locate missing persons, resulting so far in the identification of 332 missing persons. Our forensic experts are very active here in Kosovo. And despite the still ongoing pandemic, our staff have remained embedded in the Kosovo Institute of Forensic Medicine, working hand in hand with local counterparts and sharing their knowledge with them. Such knowledge and expertise can only be acquired through hard work, dedication, and close cooperation in every step of the process.

Still, as EU we should continue to demand more progress on the issue of missing persons. This is a fundamental human right. Relatives are entitled to know what happened and relevant authorities everywhere have an international and legal obligation to do all they can. Political differences and blame games should be put aside to resolve the fate of all missing persons, regardless of their background, ethnicity or religion. To make more progress and establish the fate of the missing, there needs to be willingness from all sides to share information, move forward and solve all outstanding cases, despite well-known difficulties and differences.

As a civilian CSDP mission, EULEX is here to help and support. But transitional justice is a process that can only be successful if it is jointly owned by all sides. It requires engagement and willingness to cooperate and share all available information. The families of the missing are entitled to have the answers they deserve.

I think I am speaking on behalf of all our staff members when I say that the Mission’s Forensic Team in the Kosovo Institute of Forensic Medicine is not just a unit in EULEX. Their work is not only important to the Mission itself, but above all to people whose lives changed forever after losing a loved one. Not knowing what happened to your child, partner, parent or relative is excruciating and our work is focused on providing answers.

Families and friends of missing persons from the war in Kosovo or anywhere else in the former Yugoslavia deserve no less.'

Lars-Gunnar Wigemark1

Head of the European Union Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo (EULEX)

EULEX’s mandate in a nutshell

The European Union Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo (EULEX) works shoulder to shoulder with Kosovo’s rule-of-law institutions to achieve a common goal: strengthening Kosovo’s capacity to meet its human rights obligations by making Kosovo’s justice system more accessible and fair to everyone, while increasing public trust in rule-of-law institutions.

EULEX was launched in 2008 as the largest civilian mission under the Common Security and Defence Policy of the European Union. EULEX’s is supporting Kosovo’s rule of law institutions on their path towards increased effectiveness, sustainability, multi-ethnicity and accountability, free from political interference and in full compliance with international human rights standards and best European practices. The Mission has a broad mandate covering many areas, such as monitoring the justice and correctional systems, facilitating the implementation of existing agreements of the EU-facilitated Belgrade-Pristina Dialogue, acting as Kosovo’s second security responder after the Kosovo Police and before NATO’s KFOR, managing a residual witness protection programme, facilitating international police cooperation between Kosovo and INTERPOL, EUROPOL and Serbia, and assisting the Kosovo Specialist Chambers and Specialist Prosecutor’s Office with logistic and operational support. In line with its current mandate, the Mission will continue to work shoulder to shoulder with Kosovo’s rule-of-law institutions to achieve a common goal: to make Kosovo’s justice system accessible to everyone and trustworthy for the public.

1 Lars-Gunnar Wigemark took office in January 2020.