China carbon neutrality in 2060: a possible game changer for climate

While we in Europe are currently facing a fast worsening ‘second wave’ of the pandemic, we should not lose out of sight the climate crisis that threatens humanity. I have witnessed recently the damage it is already causing in Africa and the storms Alex and Barbara that have hit Europe are another reminder - if any reminder is needed - of the danger we face.

Europe is at the forefront on climate change

The European Green Deal is a central focus of this Commission’s mandate. We have already decided to aim for climate neutrality in 2050 and we are currently discussing to raise the level of our ambition for reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. The Next Generation EU recovery plan has also been built around this priority.

“We can only tackle climate change effectively with a global approach in a multilateral framework.“

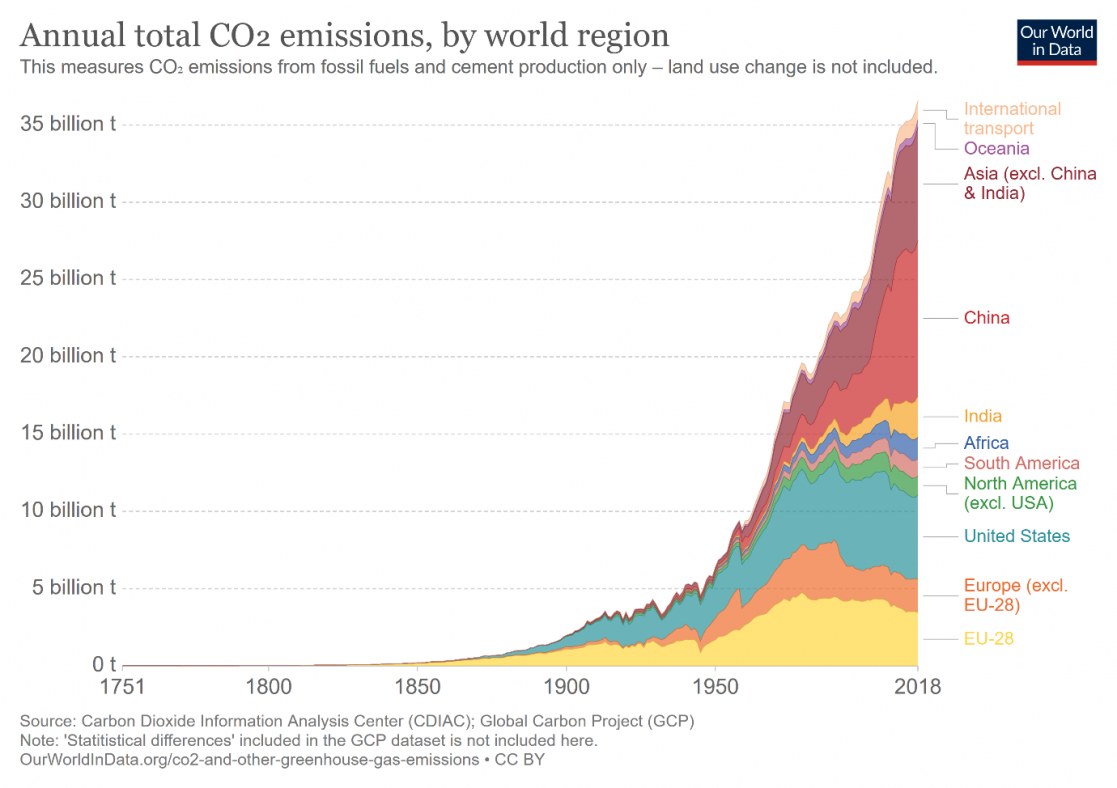

However, we must be aware of our limits in this area as the European Union is responsible for only 7% of global greenhouse gas emissions. We can only tackle climate change effectively with a global approach in a multilateral framework.

The question of the role of developing countries

Since the Rio Summit in 1992, one of the main difficulties in reaching global agreements has been around the question which role developing countries, in particular China, should play. Originally, developing countries considered, in a way that had merit, that the main responsibility for climate change lay with the developed countries and that therefore they should make the necessary efforts. However, this exclusion of developing countries also led the United States to refuse to ratify the Kyoto Protocol in 1997.

Economic developments and global changes over the past 30 years have profoundly modified the situation. Given China’s technological prowess (space exploration, cutting-edge military technology, AI), its continued self-definition as a ‘developing country’ looks more and more anachronistic and self-serving: China is an international player ready to step up on its responsibilities. However, by 2014, China agreed to make commitments on the limitation of its greenhouse gas emissions, paving the way for the Paris Agreement in 2015.

The Paris agreement breakthrough

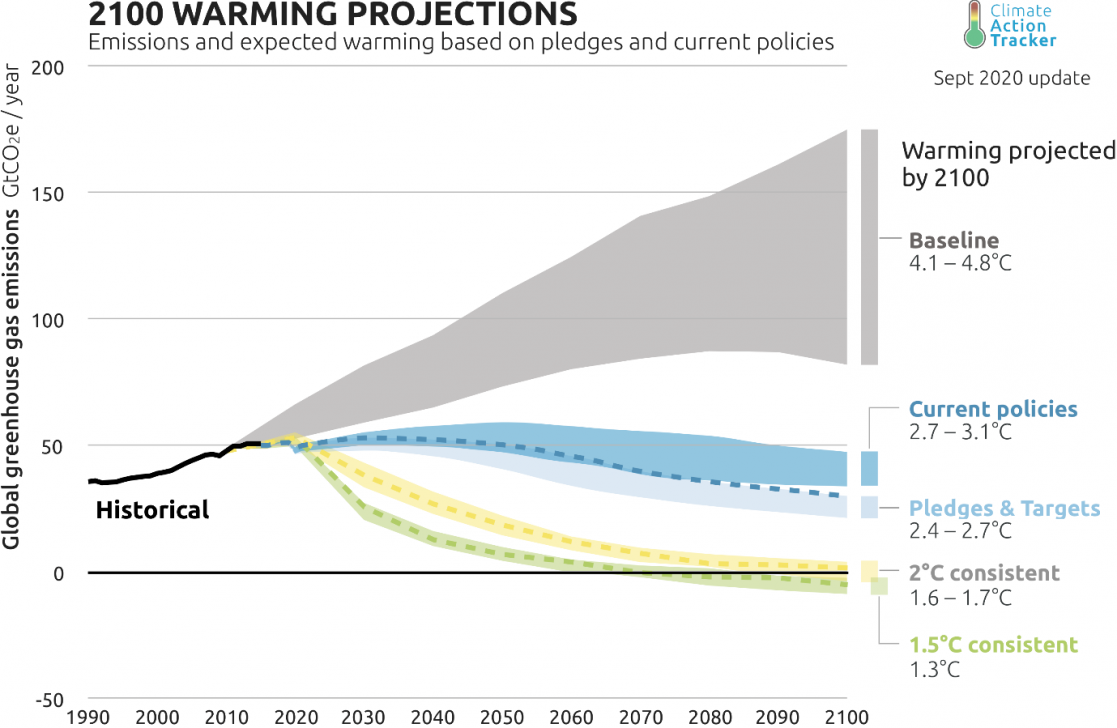

While the Paris Agreement was a true breakthrough, the scientists are clear that, for the time being the commitments made by the different countries under that agreement are still insufficient to achieve the goal of keeping global temperature rise to below 2°C by the end of the century. Given that China accounts now for 27% of global greenhouse gas emissions (while the US emits 14%, and the EU-27 and India with 7% each), its reduction efforts are absolutely critical. In addition to that, its economy is expected to continue growing and it plays a leadership role vis-à-vis emerging and developing economies on their climate stance.

“The commitments actually made under the Paris Agreement are insufficient to achieve the goal of keeping temperature rise to below 2°C by the end of the century.”

During his speech to the UN General Assembly on 22 September 2020, the Chinese President Xi Jinping announced two elements in the fight against climate change: ‘We aim to have CO2 emissions peak before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060’. The ‘peaking before 2030’ goal was anticipated but not the carbon neutrality before 2060: the announcement was made without prior trailing. Under current policies, the world would be about 2.7 degrees Celsius warmer by 2100 (we are now at 1.1°C) according to climate modellers. If China were to achieve its new goal, it would lop off 0.3 degrees off that trajectory. This is a major step.

This year, parties to the Paris Agreement are expected to issue mid-century targets. By doing this announcement, China wants to position itself vis a vis the United States as a defender of multilateralism and follower of global rules. The reality is more complex – I have spoken in the past about “selective multilateralism” or a “pick-and-choose” approach. We will watch whether this announcement was tailored for international consumption or whether carbon neutrality become really a key feature in the upcoming Five Years Plan to be discussed at the end of the month.

“The simple fact that China acknowledges the dramatic threat of climate change and that we need more action is of paramount importance.”

However, the simple fact that China acknowledges the dramatic threat of climate change and that we need more action is of paramount importance. From a domestic viewpoint, the set of challenges to address on the climate and environmental front is such that there is a sense of social urgency inside the country. In spite of this, reaching the new target will be a tremendous challenge: in China fossil fuels represent 90 % of all energy supplies and coal, the most carbon-intensive of all, generates two-thirds of electricity. In 2018, China released 590 kg of CO2 equivalent per 1000 dollars of GDP, compared to 370 for the US and 230 for the EU.

Given China’s traditional penchant for caution in making international commitments, the announcement also suggests that the leadership is confident that technological progress in energy efficiency and the cost of renewable energy can make carbon neutrality attainable, without hampering China’s economic development.

China wants to become an “electrostate”

There are also immense opportunities linked to the new green technologies where China has taken a leading position. Today, Chinese firms produce more than 70% of the world’s solar modules, 69% of lithium-ion batteries and 45% of wind turbines. They also control much of the refining of minerals critical to clean energy, such as cobalt and lithium. An ambitious long-term goal will provide a further spur for the development of these technologies. Instead of a petro-state, the People’s Republic may become an “electro-state”. This will have huge geopolitical consequences.

“Setting an ambitious objective is important. However, what matters is delivering results and China has so far not detailed how it will achieve its 2060 target.”

During the last months, the EU urged China to step up its climate ambition and we are happy to hear the announcement going in this direction. Setting an ambitious objective is important. However, what matters is delivering results and China has so far not detailed how it will achieve its 2060 target. On 14 September in the latest VTC between the EU and Chinese Leadership, it was agreed to set up a climate and environment dialogue to go further in this field. This dialogue could focus on the pathways to get to net-zero emissions. Prominent topics should be the phasing out of coal, the role of carbon pricing, the rollout of hydrogen. In addition, the dialogue could prepare the ground for global action on methane emissions.

“China should cease its financing of fossil-fuel based energy supply in third countries, starting with coal.”

It is also not just about China’s domestic energy choices: 44 % of China’s investment support in the framework of the Belt and Road initiative relates to energy. This has resulted in the construction of many fossil-fuelled power plants. In keeping up with its domestic aspirations, China should cease its financing of fossil-fuel based energy supply in third countries, starting with coal. This question should also be high on the agenda of the EU-China dialogue and for our preparation of COP 26.

The need for high ambition coalitions

We seek high ambition coalitions with countries that share our determination to live up to the objectives of the Paris Agreement. We have always said that we need to deploy a climate diplomacy to share our efforts with the rest of the world especially with great emitters and, naturally, we want to work closely with China on that issue. It could exert strong pressure on other emitters to increase their ambitions, notably in Asia, a continent accounting for more than half of global emissions, but also in the Americas. It could turn 2021 into a successful year for climate action, culminating in COP-26 in November in Glasgow.

“We need to deploy a climate diplomacy to share our efforts with the rest of the world especially and, naturally, we want to work closely with China on that issue.”

It is obvious that China’s promising announcement on climate change comes at a time when there are also significant and in fact growing differences between us, be it the situation in Hong Kong, the treatment of the Uighurs, or the lack of reciprocity in our trade and investment relations. This reminds us of the complexity of our relationship with China: it is both an economic competitor and systemic rival, whose political system is built on values that are different from ours; but also a partner for tackling the colossal challenges of the 21st century in a multilateral framework.

“China is both an economic competitor and systemic rival and a essential partner for tackling the colossal challenges of the 21st century in a multilateral framework.”

I have argued previously that we cannot reduce the complexities of the EU-China relationship to a binary choice. It is not either/or, but both/and. We can and should push back strongly in areas where China’s behaviour goes against our interest or universal values and develop our ‘strategic autonomy’, while at the same time also working closely with China to deal with global challenges and deliver global public goods – the fight against climate change being perhaps the single clearest example of this.